Third-Generation Solar Cell Technologies

Third-generation solar cells are advanced photovoltaic technologies designed to overcome the limitations of both first- and second-generation solar cells, focusing on improving efficiency, reducing costs, and utilizing novel materials and mechanisms for energy conversion. Unlike first-generation (traditional silicon-based) and second-generation (thin-film) technologies, third-generation solar cells aim to break through the theoretical efficiency limits imposed on earlier generations, such as the Shockley-Queisser limit, by employing innovative approaches.

Third-generation solar technologies include:

- OPVs

- Copper zinc tin sulphide (CZTS)

- Perovskite solar cells

- Dye-sensitised solar cells (DSSCs)

- Quantum dot solar cells

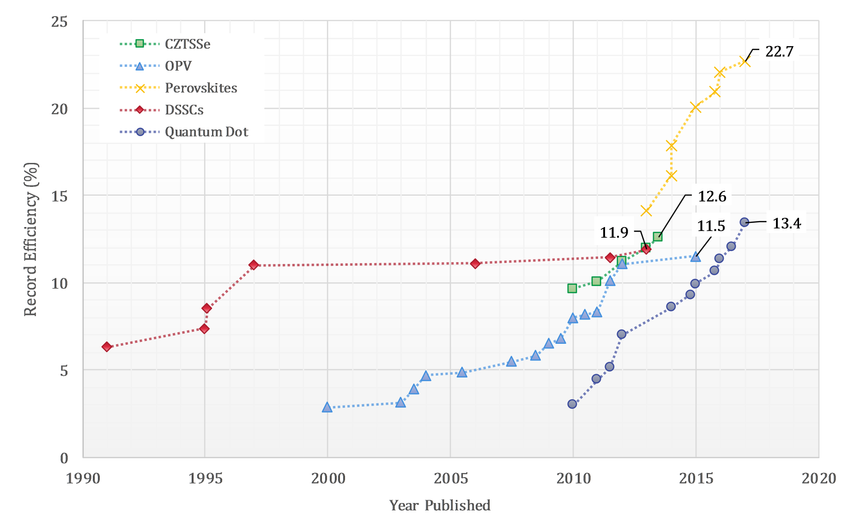

Whilst most second-generation solar technologies have been in research since the late 1970s, third-generation technologies are generally (with the exception of DSSCs) more modern offerings. As such, they are typically described as ‘emerging’ technologies. Record efficiencies achieved (over time) for different third-generation technologies can be seen in the figure, with most being considerably lower than c-Si or second-generation technologies. The main advantages of these materials are their tunability and abundant components. As research progresses, record efficiencies of several technologies are likely to continue growing.

Comparison of Third-Generation Solar Cell Technology

When comparing solar cell technologies there are a few factors that should be considered, including:

- typical efficiency

- cost

- weight

- stability to a range of environmental factors

- scalability

- environmental impact

The efficiencies achieved for a technology - in comparison to the maximum possible theoretical efficiency (Shockley-Queisser efficiency limit) - are also important, (as can be seen in the figure). This is especially so when considering the vast number of research years spent achieving this efficiency.

Perovskite solar cells are currently the most efficient third generation solar cell technology by quite a margin. All the others are managing to achieve similar efficiencies in the low teens. This is cutting edge research and so we expect to see ever increasing efficiencies being achieved.

The environmental impact of second-generation solar technology installations can be assessed with factors such as greenhouse gas emissions/global warming potential (GHG/GWP) or energy payback time (EPBT) - discussed more thoroughly in the companion article. However, measuring these values is more difficult with technologies that are yet to be manufactured on a large scale (such as CZTS). Modelled factors are shown in the figure below, although these obviously are very dependent on multiple assumptions and factors and have a higher level of uncertainty than real life values. When considering large-scale potential and environmental impact, there are several other important factors that are not discussed here - such as freshwater use, eco-toxicity, and ease of recycling.

Copper Zinc Tin Sulphide (CZTS)

CZTS cells use an active layer with the general form Cu2ZnSnS4 and a kesterite crystal structure11 (shown in the figure below). These cells have many similarities with second-generation copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) cells. However, they use significantly more abundant and non-toxic materials, and avoid using toxic cadmium or rare indium. Their use of readily-available materials is an advantage shared with OPVs, alongside a bandgap that can be easily tuned (in this case from 1.0 to 1.6eV11) by varying component stoichiometry. The record efficiency for a pure CZTS cell is 11.0%.12 However, this has been exceeded thanks to the inclusion of selenium to form a CZTSSe cell with an efficiency of 12.6%.13

Both CZTS and CZTSSe are complex materials that are difficult to optimise. Furthermore, material quality can limit the efficiencies of cells.14 In particular, this is due to a tendency for the material to form point defects through ‘cation disorder’.15 Inclusion of selenium also introduces issues in terms of material abundance and toxicity, and there have been few significant improvements in efficiencies in recent years of both variants. As with OPVs, CZTS remains attractive due to low GHG values and energy payback time, but is limited by poor efficiency.

Perovskite Solar Cells

Perovskite solar cells are covered in detail in the Ossila guide Perovskite Solar Cells: An Introduction. In short, perovskite materials are based on a generic ABX3 structure, where A is an organic cation such as methylammonium (CH3NH3+), B is an inorganic cation, typically lead (Pb2+) and X is a halogen anion, such as chloride (Cl-) or iodide (I-). Perovskites are especially notable for their rapid rise in published efficiencies and having achieved performances that are comparable to second-generation inorganic cells, clearly a significant advantage over other third-generation solar technologies.

As with CZTS and OPVs, perovskites are advantageous compared to CdTe or CIGS because they use cheaper, abundant materials, and have a tunable band gap. However, they still have notable stability issues, particularly sensitivity to moisture11 and concerns in regards to toxicity, especially due to the water-solubility of the toxic compounds - potentially leading to environmental exposure. Several lifecycle analyses of perovskites have produced modelled GHG and EPBT values which are significantly larger than those of OPVs4,6,16 (which is an obvious area of improvement in terms of manufacture optimisation), but most conclude that the lead component has negligible eco-toxicity effects.

Perovskites have strong potential for use in tandem cells with silicon, and their high growth rate suggests that efficiencies may continue to rise significantly.14 Thus, obstacles to commercial adoption are mainly improvement of stability and environmental impact.

Dye-Sensitised Solar Cells (DSSCs)

DSSCs are the longest-standing third-generation solar technology. They are based on organic dye-absorbers, such as N719 dye, in a liquid electrolyte. Many of their features and advantages overlap with those of OPVs - namely, abundant, solution-processable materials, and the potential for flexible and transparent devices. The two systems have also achieved similar certified efficiencies approaching 12%1 and small scale research efficiencies exceeding 13%.17,18 Despite this, advances on the record-certified efficiency and research-scale efficiency for DSSCs have not been exceeded since 2012 and 2014 respectively, which suggests a low potential for further improvements.

DSSCs can also suffer from instability issues. Mainly, these issues are temperature instability and solvent permeation19 of the liquid electrolyte. Theoretically, multiple dyes can be used to capture a wider range of the solar spectrum, but this results in complicated redox chemistry that can be difficult to optimise. As with OPVs, DSSCs are best suited to low-cost, niche applications, (especially those requiring a variety of colours),14 but lower efficiencies may restrict their development in the future.

Quantum Dot Solar Cells

Quantum dot solar cells encompass a variety of technologies based on semiconductor nanocrystals (most often metal chalcogenide nanocrystals such as PbS or PbSe), with the record efficiency achieved by a cell based on a CsPbI3 system.13 These share advantages with OPVs in terms of low-temperature solution-processable manufacture and easily tunable band gap,11 dependant on component choice, but often use toxic or rare materials, such as selenium. Tunable band gaps, dependent on size, could allow multi-junction cells using a single material.20 Difficulties in application include size distribution of nanoparticles leading to a distribution of band gaps, resulting in large voltage loss. Regardless, efficiencies have risen rapidly since initial publication, and certified efficiencies now exceed those of OPVs. With better understanding, efficiencies are likely to continue rising. If stability and ease of manufacture improve with alongside, quantum dots may become a promising technology for commercialisation.

Summary

Whilst OPVs have clear disadvantages (efficiency) compared to second generation solar technologies, and clear advantages in terms of environmental impact and material abundance, the comparisons are not so clear-cut for other third-generation cells. Many technologies, such as CZTS and DSSCs are similarly performing and have similar advantages, but arguably OPVs are the main low-efficiency technology that has continued to rise in reported efficiencies, especially with the advent of non-fullerene acceptors. Perovskite solar cells share the low-cost, abundant material advantages of OPVs, but have efficiencies comparable to that of second-generation technologies - and hence have received significantly more research attention in recent years. Despite this, OPVs still maintain an advantage in terms of environmental impact and material toxicity. Ultimately, it remains to be seen if this can compete with the higher efficiencies of perovskite solar cells, or if the two can co-exist in differently-suited applications.

Solar Cell Testing Kit

Learn More

Organic Solar Cells: An Introduction to Organic Photovoltaics

Organic Solar Cells: An Introduction to Organic Photovoltaics

Organic solar cells, also known as photovoltaics (OPVs), have become widely recognized for their many promising qualities. This page introduces the topic of OPVs, how they work and their development.

Read more...The rapid improvement of perovskite solar cells has made them the rising star of the photovoltaics world and of huge interest to the academic community.

Read more...References

- M. A. Green, Y. Hishikawa, E. D. Dunlop, D. H. Levi, J. Hohl-Ebinger and A. W. Y. Ho-Baillie, Solar cell efficiency tables (version 52), Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl., 2018, 26, 427–436.

- D. Hengevoss, C. Baumgartner, G. Nisato and C. Hugi, Life Cycle Assessment and eco-efficiency of prospective, flexible, tandem organic photovoltaic module, Sol. Energy, 2016, 137, 317–327.

- N. Espinosa, R. García-Valverde, A. Urbina and F. C. Krebs, A life cycle analysis of polymer solar cell modules prepared using roll-to-roll methods under ambient conditions, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2011, 95, 1293–1302.